Reflections on two weeks of rugged negotiations after 25 years of work towards a global Treaty to protect the rights of Indigenous peoples and prevent biopiracy.

The global Intellectual Property (IP) system supposedly protects inventions and incentivises individuals, companies and countries to invest in creating new things. Patents, trademarks/brands, copyrighted artistic works and trade secrets are different ways IP is protected to allow inventors and investors to be rewarded for their creations.

A lot of products, especially pharmaceuticals, as well as most food and drinks, have been based on organisms found in Nature, and sometimes they are also based on knowledge (mātauranga) passed on through generations of Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLC) where the organisms have been growing for millions of years. At least 70% of new small-molecule drugs introduced worldwide over the past 25 years came from a natural source.

Even the development of PCR tests, the basis for much of the genomics revolution over the past 40 years, was made possible by the discovery of an enzyme found in Yellowstone National Park. Ironically the US Parks Service recognised the opportunity this discovery presented and negotiated a benefit sharing arrangement for themselves, but no benefits appear to have flowed to the Shoshone, Lakota, Crow, Blackfoot, Flathead, Bannok, and Nez Perce Peoples, traditional owners of the land and water the enzyme was discovered amongst. While the Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche owned the associated patents, the company, like most similar sized multinationals, has a nice corporate statement about biopiracy and associated ethical standards. What these companies do in reality is another story.

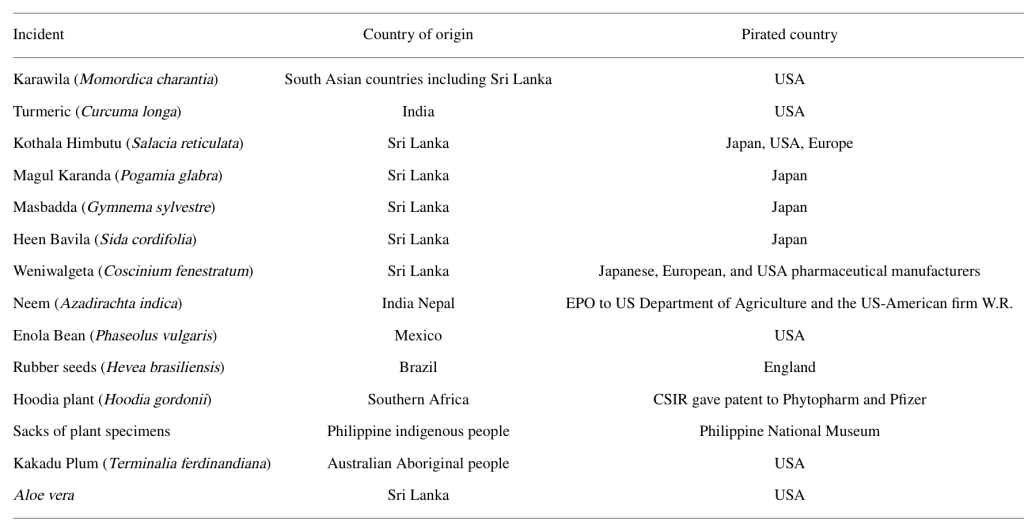

A set of examples of companies taking organisms was provided in this 2021 article:

A range of international agreements have been established over the past 35 years that recognise the rights of IPLCs as custodians of indigenous flora and fauna or ‘Genetic Resources’ (GR) , and owners of their Traditional Knowledge (TK) associated with those organisms. Frameworks and principles have been developed to promote things like Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and fair & equitable Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) arrangements.

In 1994 more than 100 countries signed the International Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) that promised to recognise the property rights of developing countries (not necessarily IPLCs). It didn’t prohibit the collection of indigenous material but recommended that Mutually Agreed Terms should be reached to share any commercial benefit that later emerges.

While agreements like the CBD have been signed by many countries – some like USA haven’t ratified it and New Zealand, Australia, USA and Canada are yet to sign on to subsequent agreements like the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS), and others that have signed don’t have particularly strong domestic legislation based on the international agreements.

25 years ago a group of countries led by Colombia promoted the possibility of a Treaty to cover IP derived from Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge (GRATK). It has taken this long to get one.

By 2010, the pharmaceutical industry was openly lobbying against the idea of being regulated to prevent biopiracy:

“Using IP (intellectual property) or the patent system to enforce compliance in the access and benefit sharing regime is a significant concern of biotech industries. There are other ways to address compliance issues than through the patent system, such as contracts and mutually agreed terms.”

The goal of this Diplomatic Conference host by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), an arm of the United Nations system that New Zealand joined in 1984, was to get a Treaty against biopiracy, and that’s what was achieved over 25 years and two weeks.

The outcome was better than many expected for IPLCs.

In the WIPO Treaty-making process, the world is divided into groups – NZ is part of ‘Group B’, a collection of the wealthiest countries including the US, EU, Japan, South Korea, Israel, Australia and Switzerland. There are other groups for Asia-Pacific, Africa, South Pacific, Central & Eastern Europe, ‘Like-Minded Countries’ (those with the highest levels of biodiversity) and China are their own group.

The groups generally come to collective positions on key issues, though individual countries can have a differing opinion, but group positions carry a lot more weight. This is a common practice in the UN system, though group composition changes between UN institutions.

The US, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland and EU were, for all intents and purposes, the voice and defenders of the ‘life sciences’ or Big Pharma(ceuticals) industry that is worth US$1.6 trillion in annual revenue and billions in profits for their shareholders.

Dominic Keating, lead negotiator for the USA and one of the staunchest opponents of any clauses that would prevent pharmaceutical companies from taking whatever they want from anywhere to maximise profits from proprietary IP covered by patents.

Fortunately, as members of Group B, the New Zealand and Australia delegations were staunch defenders of Indigenous rights and blocked their group from taking stronger positions on key clauses.

Some of the big issues of contention were:

Whether this Treaty was about indigenous rights and protecting GRs & ATK or simply a ‘transparency mechanism’ for patent applicants.

Defining what was covered in terms of IP derived from GRs and TK – a big bone of contention was whether Digital Sequence Information (data on the genes in an organism and how it works) was included.

Whether the Treaty covers just patents or includes other types of IP.

What the trigger for disclosure by applicants would be in terms of how GRATK were used in development as opposed to the final patent.

What sanctions could be applied to applicants who knowingly or unknowingly provided incorrect or incomplete information.

When the Treaty would apply from – both in terms of when the GRATK was accessed or when the patent application was made, and also how many countries needed to ratify it before it becomes operative and binding on everyone.

When it would be reviewed and who would be allowed to participate in the review – there was a strong expectation that Big Pharma’s friends would not sign and they were only participating in this process to make it as weak as possible, based on the signing ceremony. It seems this was an accurate prediction as, even after dozens of concessions to accommodate their demands, the US, Japan and South Korea didn’t even sign the Final Act (like confirming the minutes of what was agreed).

Having the privilege of participating in the Indigenous Caucus was one of the most profound experiences of my life. I felt like an imposter or at least opportunist, coming in at literally the last minute – well, last two weeks – of a 25 year process.

Part way through the first week the Presidents of the two Committees, that were each focused on half of the draft Articles to work through in smaller groups, made the decision to proceed only in English. This was partly understandable given the challenges of interpretation and translation, but a terrible blow to non-English speaking members of all delegations, including at least half of the Indigenous Caucus. I’m sure there will be more commentary on the Caucus process, but the English-only negotiations meant that I was able to contribute a lot more than may have otherwise been required.

While all members of the Indigenous Caucus still had pivotal roles in liaising with their respective country delegations and others they could connect with, the problematic and powerful countries blocking Indigenous Caucus and other regional groups’ priorities were in the Group B that also contained New Zealand and Australia, who had Indigenous members of their delegations and positive relationships with members of the Indigenous Caucus. There were 1,200 delegates at the Conference and I was the only Māori member of the Indigenous Caucus, so took an active role liaising with New Zealand, but also other countries like the United Kingdom and USA (who also had an Indigenous member of their delegation – Keone Nakoa from Hawai’i who is also Deputy Assistant Secretary for Insular and International Affairs).

One of the most significant signs of malevolent intent by these states came in closing plenary session. Every other country used the opportunity to thank the Conference leaders, the staff who organised the process over 25 years and the good will of all countries to participate and build consensus (right up to 3am on the last night!). The USA delegation took their turn almost at the end, and used their allocated time (plus some more) to instead outline their interpretation of the most contentious articles to try and reframe the agreements reached and out their own slant on each provision negotiated over many years. It was a terrible display of poor form and they were followed by Japan, Switzerland and South Korea who echoed support for the US versions of the Treaty.

By the end of the Conference on Friday 24 May 2024, the Final Act had been signed by all but this handful of WIPO members and 28 signed the Treaty itself, a precursor to ratifying the agreements.

“Today we made history in many ways. This is not just the first new WIPO Treaty in over a decade but also the first one that deals with genetic resources and traditional knowledge held by Indigenous Peoples as well as local communities,” said Daren Tang, the agency’s Director-General.

Once ratified by 15 contracting parties, the Treaty will establish an international legal framework requiring patent applicants to disclose the origin of genetic resources and the associated traditional knowledge used in their inventions.

Lots of compromises were made over the two weeks, some say too many – the fact that DSIs are not included explicitly, that non-signatory countries could try to have a say on future changes to the Treaty, that Free Prior and Informed Consent and data sovereignty principles are not baked into the first version of the Treaty, and weak commitments to supporting IPLCs and developing countries to participate in the Assembly of the Treaty, are all areas of huge concern for IPLCs. On the other hand, thanks to staunch advocacy from the Latin American countries and Africa Group – led by the indomitable Harvard law professor Ruth Okediji for Nigeria – and the (mostly) quiet diplomacy of the New Zealand delegation in Group B, along with the tireless efforts of Indigenous Caucus co-chair Jennifer Corpuz from the Kankana-ey Igorot Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines, there are a lot of positive provisions for IPLCs:

- acknowledgment of UNDRIP for the first time in any international Treaty

- special recognitions of IPLCs and a commitment to effective participation in the future of the Treaty governance

- reduced role for non-signatory countries and non-contracting parties (including Big Pharma lobbyists)

- no commitment to establishing the global database of Genetic Resources that Japan was pushing hard for right to the end

- no provision for patent applicants to use ignorance as an excuse for not disclosing the origin of GRs and TK that their claimed inventions are based upon

- scope for Digital Sequence Information to be included in future versions of the Treaty (and already the implicit possibility to extend the scope of disclosure to DSI in some cases, where they may be used to evade disclosure)

- confirmation that IPLCs should be involved in the implementation of the Treaty (which will include areas like determining appropriate sanctions and remedies for breaches)

So, there will be lots more commentary – not least on the role of Indigenous Peoples representatives in the Treaty implementation going forward at tribal, domestic and international levels. But for now, I think most of us can celebrate there’s a global legal instrument that can be used and improved to better protect the rights and interests of Indigenous peoples, and also local communities that are holders of Traditional Knowledge.

Working it all out in our respective contexts will be challenging and exciting. My personal thanks to everyone involved and to those who helped make my participation possible including Kenzi Riboulet-Zemouli (support his important work here) and Michael Krawitz from FDM and the Cannabis Embassy, the other members of our eclectic delegation Paula (for diligent documentation and gentle diplomacy within and outside the team) and Larissa (for the energy and unquiet diplomacy to meet every country and industry delegate!). To Maui Hudson and the Te Kotahi Research Institute whānau that helped fund my travel, to Matthew Monahan who sponsored the team accommodation for three weeks in Geneva (not cheap!) and Jody Toroa and the Tū Wairua kaupapa that also contributed to our expenses – tēnei te pīki mihi kia koutou katoa. Also to my friend and mentor in these processes, Tracey Whare and the Aotearoa Indigenous Rights Trust that we’re in the process of reinvigorating to support more consistent participation by Māori, alongside iwi/hapū representatives in these global discussions, systems and instruments. 🙏🏼

For those interested, further opportunities are coming up again at WIPO in November to progress similar international instruments focused on Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions (including ‘folklore’). Māori connected to these kaupapa need to get better organised, I hope we can collaborate and coordinate more strategic involvement and presence in these processes, with support from iwi, Māori trusts and land entities, NGOs and other allied stakeholders. 👆🏼

Leave a comment